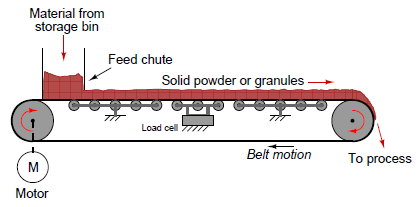

A special type of flowmeter suited for powdered or granular solids is the weigh feeder. One of the most common weigh feeder designs consists of a conveyor belt with a section supported by rollers coupled to one or more load cells, such that a fixed length of the belt is continuously weighed:

The load cell measures the weight of a fixed-length belt section, yielding a figure of material weight per linear distance on the belt. A tachometer (speed sensor) measures the speed of the belt. The product of these two variables is the mass flow rate of solid material “through” the weigh feeder:

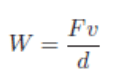

Where,

W = Mass flow rate (e.g. pounds per second)

F = Force of gravity acting on the weighed belt section (e.g. pounds)

v = Belt speed (e.g. feet per second)

d = Length of weighed belt section (e.g. feet)

A small weigh feeder (about two feet in length) is shown in the following photograph, the weigh feeder is used to feeding powdered soda ash into the water at a municipal filtration plant to neutralize pH:

In the middle of the belt’s span (hidden from view) is a set of rollers supporting the weight of the belt and of the soda ash piled on the belt. This load cell array provides a measurement of pounds of material per foot of belt length (lb/ft).

As you can see in this next picture, the soda ash powder simply falls off the far end of the conveyor belt, into the water below:

The speed sensor measures belt speed in feet per minute (ft/min). This measurement, when multiplied by the pounds-per-foot measurement sensed by the load cells, translates into a mass flow rate in units of pounds per minute (lb/min). A simple unit conversion (×60) expresses the mass flow rate in units of pounds per hour (lb/h). A photograph of this weigh feeders display screen shows these variables:

Note that the belt loading of 1.209 lb/ft and the belt speed of 0.62 feet per minute do not exactly equate to the displayed mass flow rate of 43.7 lb/h. The reason for this discrepancy is that the camera’s snapshot of the weigh feeder display screen happened to capture an image where the values were not simultaneous. Weigh feeders often exhibit fluctuations in belt loading during normal operation, leading to fluctuations in the calculated mass flow rate. Sometimes these fluctuations in measured and calculated variables do not coincide on the display screen, given the latency inherent to the mass flow calculation (delaying the flow rate value until after the belt loading has been measured and displayed).

Change-of-quantity flow measurement

Flow, by definition, is the passage of material from one location to another over time. So far this chapter has explored technologies for measuring flow rate en route from source to destination. However, a completely different method exists for measuring flow rates: measuring how much material has either departed or arrived at the terminal locations over time.

Mathematically, we may express flow as a ratio of quantity to time. Whether it is volumetric flow or mass flow we are referring to, the concept is the same: quantity of material moved per quantity of time. We may express average flow rates as ratios of changes:

Where,

W = Average mass flow rate

Q = Average volumetric flow rate

m = Change in mass

V = Change in volume

t = Change in time

Suppose a water storage vessel is equipped with load cells to precisely measure weight (which is directly proportional to mass with constant gravity). Assuming only one pipe entering or exiting the vessel, and the flow of water through that pipe will result in the vessel’s total weight changing over time:

If the measured mass of this vessel decreased from 74,688 kilograms to 70,100 kilograms between 4:05 AM and 4:07 AM, we could say that the average mass flow rate of water leaving the vessel is 2,294 kilograms per minute over that time span.

Note that this average flow measurement may be determined without any flowmeter of any kind installed in the pipe to intercept the water flow. All the concerns of flowmeters studied thus far (turbulence, Reynolds number, fluid properties, etc.) are completely irrelevant. We may measure practically any flow rate we desire simply by measuring stored weight (or volume) over time. A computer may do this calculation automatically for us if we wish, on practically any time scale desired.

Now suppose the practice of determining average flow rates every two minutes was considered too infrequent. Imagine that operations personnel require flow data calculated and displayed more often than just 30 times an hour. All we must do to achieve better time resolution is take weight (mass) measurements more often. Of course, each mass-change interval will be expected to be less with more frequent measurements, but the amount of time we divide by in each calculation will be proportionally smaller as well. If the flow rate happens to be absolutely steady, we may sample mass as frequently as we might like and we will still arrive at the same flow rate value as before (sampling mass just once every two minutes). If, however, the flow rate is not steady, sampling more often will allow us to better see the immediate “ups” and “downs” of flow behavior.

Imagine now that we had our hypothetical “flow computer” take weight (mass) measurements at an infinitely fast pace: an infinite number of samples per second. Now, we are no longer averaging flow rates over finite periods of time; instead, we would be calculating instantaneous flow rates at any given point in time.

Calculus has a special form of symbology to represent such hypothetical scenarios: we replace the Greek letter “delta” (, meaning “change”) with the roman letter “d” (meaning differential ). A simple way of picturing the meaning of “d” is to think of it as meaning an infinitesimal interval of whatever variable follows the “d” in the equation. When we set up two differentials in a quotient, we call the d/d fraction a derivative. Re-writing our average flow rate equations in derivative (calculus) form:

Where,

W = Instantaneous mass flow rate

Q = Instantaneous volumetric flow rate

dm = Infinitesimal (infinitely small) change in mass

dV = Infinitesimal (infinitely small) change in volume

dt = Infinitesimal (infinitely small) change in time

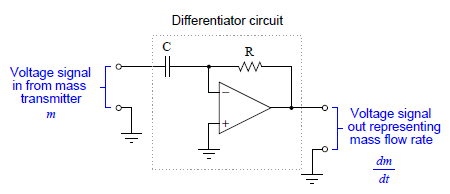

We need not dream of hypothetical computers capable of infinite calculations per second in order to derive a flow measurement from a mass (or volume) measurement. Analog electronic circuitry exploits the natural properties of resistors and capacitors to essentially do this very thing in real-time:

In the vast majority of applications, you will see digital computers used to calculate average flow rates rather than analog electronic circuits calculating instantaneous flow rates. The broad capabilities of digital computers virtually ensure they will be used somewhere in the measurement/control system, so the rationale is to use the existing digital computer to calculate flow rates (albeit imperfectly) rather than complicate the system design with additional (analog) circuitry. As fast as modern digital computers are able to process simple calculations such as these anyway, there is little practical reason to prefer analog signal differentiation except in specialized applications where high-speed performance is paramount.

Perhaps the single greatest disadvantage to inferring flow rate by differentiating mass or volume measurements over time is the requirement that the storage vessel has but one flow path in and out. If the vessel has multiple paths for the liquid to move in and out (simultaneously), any flow rate calculated on change-in-quantity will be a net flow rate only. It is impossible to use this flow measurement technique to measure one flow out of multiple flows common to one liquid storage vessel.

A simple “thought experiment” confirms this fact. Imagine a water storage vessel receiving a flow rate of 200 gallons per minute. Next, imagine that same vessel emptying water out of a second pipe at the exact same flow rate: 200 gallons per minute. With the exact same flow rate both entering and exiting the vessel, the water level in the vessel will remain constant. Any change-of-quantity flow measurement system would register zero change in mass or volume over time, consequently calculating a flow rate of absolutely zero. Truly, the net flow rate for this vessel is zero, but this tells us nothing about the flow in each pipe, except that those flow rates are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction.

List of Prominent Suppliers: ABB, Ados, AEP Transducers, Alps, Althen Sensors, Ametek, Anadolu, Andilog, Angst+Pfister, ASA-RT, Avery Weigh-Tronix, Barbal, Baumer, BCM Sensor, Bongshin Loadcell, Bosche, Brosa, Burster, Cardinal, CAS, Cleveland Motion Controls, Cometech, DFE, Dini Argeo, Dinaksa, Eagle Microsystems, Eilersen, Enerpac, Epoch, Europress, FMS, Futek, Gavin, Gerfan, GTM, Haehne, Hardy Process Solutions, HBM, Honeywell, Instron, Interface Inc, Kubota, Kyowa, LCT, Lorenz, Magtrol, Manyyear, ME, MeasureX, Megatron, Minebea intec, Omega, PCE, Precia Molen, PT, Pulseletronic, Rice Lake Weighing Systems, Rinstrum, Sartorius, Scaime, Schenck Process, Seegate Corporation, Sensocar, Sensotec, Sensotronic, Sensy, Sherborne Sensors, Siemens, Soway, Sreeka, Starrett, Stephens Mfg., Strainsert Co., Tamtron, Transducer Techniques, UTICell, Vetec, Wika, XSensors, Yuttah, Zwick/Roell