Turbine flowmeters use a free-spinning turbine wheel to measure fluid velocity, much like a miniature windmill installed in the flow stream. The fundamental design goal of a turbine flowmeter is to make the turbine element as free-spinning as possible, so no torque will be required to sustain the turbine’s rotation. If this goal is achieved, the turbine blades will achieve a rotating (tip) velocity directly proportional to the linear velocity of the fluid:

The mathematical relationship between fluid velocity and turbine tip velocity – assuming frictionless conditions – is a ratio defined by the tangent of the turbine blade angle:

For a 45-degree blade angle, the relationship is 1:1, with tip velocity equaling fluid velocity. Smaller blade angles (each blade closer to parallel with the fluid velocity vector) result in the tip velocity being a fractional proportion of fluid velocity.

Turbine tip velocity is quite easy to sense using a magnetic sensor, generating a voltage pulse each time one of the ferromagnetic turbine blades passes by. Traditionally, this sensor is nothing more than a coil of wire in proximity to a stationary magnet, called a pickup coil or pickoff coil because it “picks” (senses) the passing of the turbine blades. Magnetic flux through the coil’s center increases and decreases as the passing of the steel turbine blades presents a varying reluctance (“resistance” to magnetic flux), causing voltage pulses to equal in frequency to the number of blades passing by each second. It is the frequency of this signal that represents fluid velocity, and therefore volumetric flow rate.

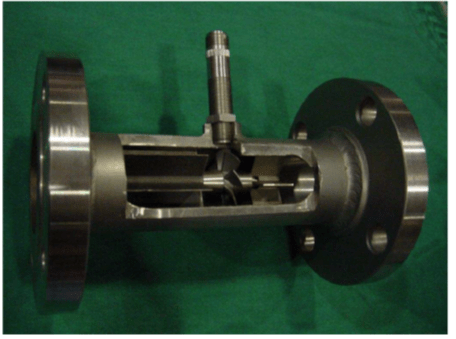

A cut-away demonstration model of a turbine flowmeter is shown in the following photograph. The blade sensor may be seen protruding from the top of the flow tube, just above the turbine wheel:

Note the sets of “flow conditioner” vanes immediately before and after the turbine wheel in the photograph. As one might expect, turbine flowmeters are very sensitive to swirl in the process fluid flow stream. In order to achieve high accuracy, the flow profile must not be swirling in the vicinity of the turbine, lest the turbine wheel spin faster or slower than it should represent the velocity of a straight-flowing fluid.

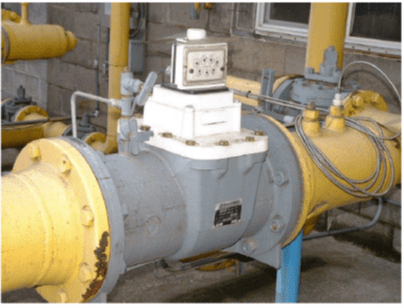

Mechanical gears and rotating cables have also been historically used to link a turbine flowmeter’s turbine wheel to indicators. These designs suffer from greater friction than electronic (“pickup coil”) designs, potentially resulting in more measurement error (less flow indicated than there actually is, because the turbine wheel is slowed by friction). One advantage of mechanical turbine flowmeters, though, is the ability to maintain a running total of gas usage by turning a simple odometer-style totalizer. This design is often used when the purpose of the flowmeter is to track total fuel gas consumption (e.g. natural gas used by a commercial or industrial facility) for billing. Pressure and temperature compensation is relevant to turbine flowmeters in gas flow applications because the density of the gas is a strong function of both pressure and temperature. The turbine wheel itself only senses gas velocity, and so these other factors must be taken into consideration to accurately calculate mass flow (or standard volumetric flow; e.g. SCFM).

The following photograph shows three AGA7-compliant installations of turbine flowmeters for measuring the flow rate of natural gas:

Note the pressure-sensing and temperature-sensing instrumentation installed in the pipe, reporting gas pressure and gas temperature to a flow-calculating computer (along with turbine pulse frequency) for the calculation of natural gas flow rate.

Less-critical gas flow measurement applications may use a “compensated” turbine flowmeter that mechanically performs the same pressure- and temperature-compensation functions on turbine speed to achieve true gas flow measurement, as shown in the following photograph:

The particular flowmeter shown in the above photograph uses a filled-bulb temperature sensor (note the coiled, armored capillary tube connecting the flowmeter to the bulb) and shows total gas flow by a series of pointers, rather than gas flow rate.

A variation on the theme of turbine flow measurement is the paddlewheel flowmeter, a very inexpensive technology usually implemented in the form of an insertion-type sensor. In this instrument, a small wheel equipped with “paddles” parallel to the shaft is inserted in the flow stream, with half the wheel shrouded from the flow. A photograph of a plastic paddlewheel flowmeter appears here:

A surprisingly sophisticated method of “pickup” for the plastic paddlewheel shown in the photograph uses fiber-optic cables to send and receive light. One cable sends a beam of light to the edge of the paddlewheel, and the other cable receives light on the other side of the paddlewheel. As the paddlewheel turns, the paddles alternately block and pass the light beam, resulting in a pulsed light beam at the receiving cable. The frequency of this pulsing is, of course, directly proportional to the volumetric flow rate.

The external ends of the two fiber optic cables appear in this next photograph, ready to connect to a light source and light pulse sensor to convert the paddlewheel’s motion into an electronic signal:

A problem common to all turbine flowmeters is that of the turbine “coasting” when the fluid flow suddenly stops. This is more often a problem in batch processes than in continuous processes, where the fluid flow is regularly turned on and shut off. This problem may be minimized by configuring the measurement system to ignore turbine flowmeter signals any time the automatic shutoff valve reaches the “shut” position. This way, when the shutoff valve closes and fluid flow immediately halts, any coasting of the turbine wheel will be irrelevant. In processes where the fluid flow happens to pulse for reasons other than the control system opening and shutting automatic valves, this problem is more severe.

Another problem common to all turbine flowmeters is the lubrication of the turbine bearings. The frictionless motion of the turbine wheel is essential for accurate flow measurement, which is a daunting design goal for flowmeter manufacturing engineers. The problem is not as severe in applications where the process fluid is naturally lubricating (e.g. diesel fuel), but in applications such as natural gas flow where the fluid provides no lubrication to the turbine bearings, external lubrication must be supplied. This is often a regular maintenance task for instrument technicians: using a hand pump to inject light-weight “turbine oil” into the bearing assemblies of turbine flowmeters used in gas service.

Process fluid viscosity is another source of friction for the turbine wheel. Fluids with high viscosity (e.g. heavy oils) will tend to slow down the turbine’s rotation even if the turbine rotates on frictionless bearings. This effect is especially pronounced at low flow rates, which leads to a minimum linear flow rating for the flowmeter: a flowrate below which it refuses to register proportionately to fluid flow rate.

List of Prominent Manufacturers: Adam Pumps, Alldoo, Anderson-Negele, Badger Meter, Bopp & Reuther Messtechnik, Burak, Cameron, Dwyer, Emco Controls, FeeJoy, FloMec, FlowTech, Flux, Gavin, Hoffeer Flow Controls, Flowmeters, Holykell, Honeywell, Indumart, Kem-Kuppers, Kobold, Kracht, Lutz, Medenus, Metri, Omega, Merret, Oval, Pietro Fiorentini, Piusi, Process Control Devices, RMG, Sensia, Sensotec, Sika, Supmea, Tecfluid, Toshniwal, UFM, Val.Co, Zenner