A very different style of the variable-area flowmeter is used extensively to measure flow rate through open channels, such as irrigation ditches. If an obstruction is placed within a channel, any liquid flowing through the channel must rise on the upstream side of the obstruction. By measuring this liquid level rise, it is possible to infer the rate of liquid flow past the obstruction.

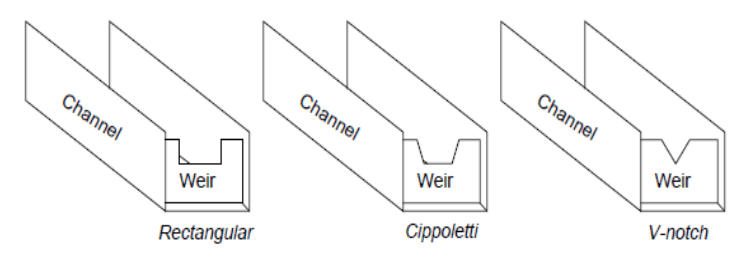

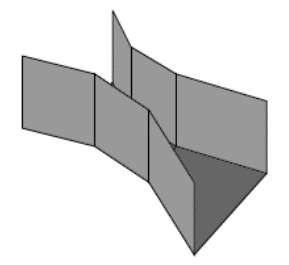

The first form of the open-channel flowmeter is the weir, which is nothing more than a dam obstructing the passage of liquid through the channel. Three styles of the weir are shown in the following illustration; rectangular, Cippoletti, and V-notch:

A rectangular weir has a notch of a simple rectangular shape, as the name implies. A Cippoletti weir is much like a rectangular weir, except that the vertical sides of the notch have a 4:1 slope (rise of 4, run of 1; approximately a 14-degree angle from vertical). A V-notch weir has a triangular notch, customarily measuring either 60 or 90 degrees.

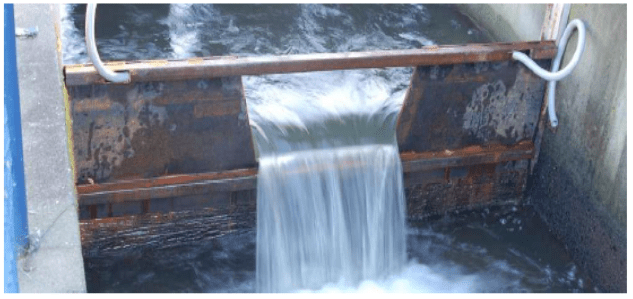

The following photograph shows water flowing through a Cippoletti weir made of 1/4 inch steel plate:

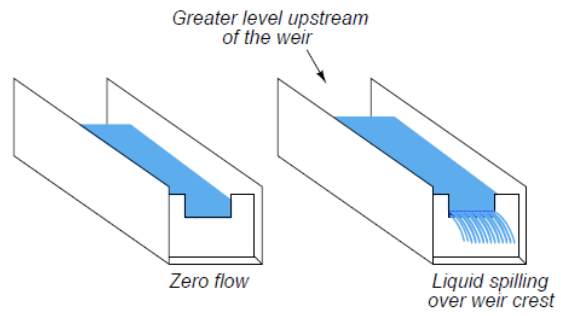

At a condition of zero flow through the channel, the liquid level will be at or below the crest (lowest point on the opening) of the weir. As the liquid begins to flow through the channel, it must spill over the crest of the weir in order to get past the weir and continue downstream in the channel. In order for this to happen, the level of the liquid upstream of the weir must rise above the weir’s crest height. This height of liquid upstream of the weir represents a hydrostatic pressure, much the same as liquid heights in piezometer tubes represent pressures in a liquid flow stream through an enclosed pipe. The height of liquid above the crest of a weir is analogous to the pressure differential generated by an orifice plate. As liquid flow is increased, even more, a greater pressure (head) will be generated upstream of the weir, forcing the liquid level to rise. This effectively increases the cross-sectional area of the weir’s “throat” as a taller stream of liquid exits the notch of the weir.

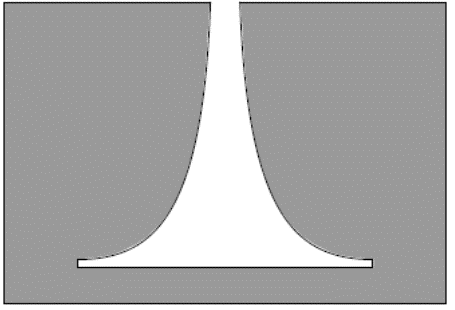

As you can see from a comparison of characteristic flow equations between these three types of weirs, the shape of the weir’s notch has a dramatic effect on the mathematical relationship between flow rate and head (liquid level upstream of the weir, measured above the crest height). This implies that it is possible to create almost any characteristic equation we might like just by carefully shaping the weir’s notch in some custom form. A good example of this is the so-called proportional or Sutro weir:

Sutro weirs are not used very often, due to their inherently weak structure and tendency to clog with debris.

A rare example of a Sutro weir appears in the following photograph, discharging flow from a lake into a stream:

The metal plates forming the weir’s shape are quite thick (about 1/2 inch) to give the weir sufficient strength. A good construction practice seen on this Sutro weir, but recommended on all weir designs, is to bevel the downstream edge of the weir plate much like a standard orifice plate profile. The beveled edge provides a minimum-friction passageway for the liquid as it spills through the weir’s opening.

A variation on the theme of a weir is another open-channel device called a flume. If weirs may be thought of as open-channel orifice plates, then flumes may be thought of as open-channel venturi tubes:

Like weirs, flumes generate upstream liquid level height changes indicative of flow rate. One of the most common flume designs is the Parshall flume, named after its inventor R.L. Parshall when it was developed in the year 1920.

Flumes are generally less accurate than weirs, but they do enjoy the advantage of being inherently self-cleaning. If the liquid stream being measured is drainage- or wastewater, a substantial amount of solid debris may be present in the flow that could cause repeated clogging problems for weirs. In such applications, flumes are often the more practical flow element for the task (and more accurate over the long term as well, since even the finest weir will not register accurately once fouled by debris).

Once a weir or flume has been installed in an open channel to measure the flow of liquid, some method must be employed to sense upstream liquid level and translate this level measurement into a flow measurement. Perhaps the most common technology for weir/flume level sensing is ultrasonic. Ultrasonic level sensors are completely non-contact, which means they cannot become fouled by the process liquid (or debris in the process liquid). However, they may be “fooled” by foam or debris floating on top of the liquid, as well as waves on the liquid surface.

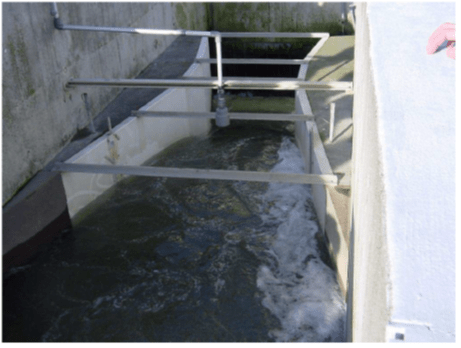

The following photograph shows a Parshall flume measuring effluent flow from a municipal sewage treatment plant, with an ultrasonic transducer mounted above the middle of the flume to detect the water level flowing through:

Once the liquid level is successfully measured, a computing device is used to translate that level measurement into a suitable flow measurement (and in some cases even integrate that flow measurement with respect to time to arrive at a value for total liquid volume passed through the element, in accordance with the calculus relationship.

A significant advantage that weirs and flumes have over other forms of flow measurement is exceptionally high rangeability: the ability to measure very wide ranges of flow with a modest pressure (height) span. Another way to state this is to say that the accuracy of a weir or flume is quite high even at low flow rates.

The practical advantage this gives weirs and flumes is the ability to maintain high accuracy of flow measurement at very low flow rates – something a fixed-orifice element simply cannot do. It is commonly understood in the industry that traditional orifice plate flowmeters do not maintain good measurement accuracy much below a third of their full-range flow (a rangeability or turndown of 3:1), whereas weirs (especially the V-notch design) can achieve far greater turndown (up to 500:1 according to some sources).