Importance of proper valve sizing

The flow coefficient of a control valve (Cv) is a numerical value expressing the number of gallons per minute flow of water the valve will pass with a constant pressure drop of 1 PSI from inlet to outlet. This rating is usually given for the valve in its wide-open state. For example, a control valve with a Cv rating of 45 should flow 45 gallons per minute of water through it with a 1 PSI pressure drop when wide open. The flow coefficient value for this same control valve will be less than 45 when the valve position is anything less than fully open. When the control valve is in the fully shut position, its Cv value will be zero. Thus, it should be understood that Cv is truly a variable – not a constant – for any control valve, even though control valves are often specified simply by their maximum flow capacity.

As previously shown, the basic liquid-flow equation relating volumetric flow rate to pressure drop and specific gravity is:

Where,

- Q = Volumetric flow rate of liquid (gallons per minute, GPM)

- Cv = Flow coefficient of valve

- P1 = Upstream pressure of the liquid (PSI)

- P2 = Downstream pressure of the liquid (PSI)

- Gf = Specific gravity of the liquid

It should be obvious that any control valve must be sized large enough (i.e. possess sufficient maximum Cv capacity) to flow the greatest expected flow rate in any given process installation. A valve that is too small for an application will not be able to pass enough process fluid through it when needed.

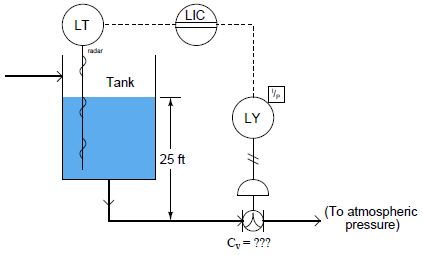

Given this fact, it may seem safe to choose a valve sized much larger than what is needed, just to avoid the possibility of not having enough flow capacity. For instance, consider this control valve sizing problem, where a characterized ball valve controls the flow rate of water out of a surge tank to maintain a constant water level 25 feet higher than the height of the valve:

According to the process engineers, the maximum expected flow rate for this valve is 470 GPM. What should the maximum Cv rating be for this valve? To begin, we must know the expected pressure drop across the valve. The 25-foot water column height upstream provides us with the means to calculate P1 by using the formula for calculating hydrostatic pressure (the pressure generated by a vertical column of liquid under the influence of gravity):

P = γh

P1 = (62.4 lb/ft3)(25 feet)

P1 = 1560 PSF = 10.8 PSI

There is no need to calculate P2 since the P&ID shows us that the downstream side of the valve is vented to the atmosphere, and is thus 0 PSI gauge pressure. This gives us a pressure drop of 10.8 PSI across the control valve, with an expected maximum flow rate of 470 GPM. Manipulating our flow capacity equation to solve for Cv:

This tells us we need a control valve with a Cv value of at least 143 to meet the specified (maximum) flow rate. A valve with insufficient Cv would not be able to flow the required 470 gallons per minute of water with only 10.8 PSI of pressure drop.

Does this mean we may safely over-size the valve? For the sake of argument, would there be any problem with installing a control valve with a Cv value of 300? The general answer to these questions is that oversized valves may create other problems. Not only is there the possibility of allowing too much flow under wide-open conditions (consider whatever process vessels and equipment lie downstream of the oversized valve), but also that the process will be difficult to control under low-flow conditions.

In order to understand how an oversized control valve leads to unstable control, an exaggerated example is helpful to consider: imagine installing a fire hydrant valve on your kitchen sink faucet. Certainly, a wide-open hydrant valve would allow sufficient water to flow into your kitchen sink. However, most of this valve’s usable range of throttling will be limited to the first percent of stem travel. After the valve is opened just a few percent from fully shut, restrictions in the piping of your house’s water system will have limited the flow rate to its maximum, thus rendering the rest of the valve’s stem travel capacity utterly useless. It would be challenging indeed to try filling a drinking cup with water from this hydrant valve: just a little bit too much stem motion and the cup would be subjected to a full-flow stream of water!

An oversized valve is therefore an overly-sensitive valve from the perspective of the control system driving it. With the upper end of the valve’s travel being useless for control (having little or no effect), all the throttling action must take place within the first few percent of stem motion. This makes precise control of flow rate more challenging than it should be. Typical valve problems such as stem friction, hysteresis, and calibration error, therefore, become amplified when the valve is over-sized because any amount of imprecision in stem positioning becomes a greater percentage of the valve’s useful travel range than if the valve were properly sized and able to use its full range of motion.

Control valve over-sizing is a common problem in the industry, often created by future planning for expanded process flow. “If we buy a large valve now,” so the reasoning goes, “we won’t have to replace a smaller valve with a large valve when the time comes to increase our production rate.” In the interim period when that larger valve must serve to control a meager flow rate, however, operational problems caused by poor control quality may end up costing the business more than the cost of an additional valve. The key here, as in so many other applications in business, is to carefully consider costs over the lifespan of the device, not just the initial (capital) expense.

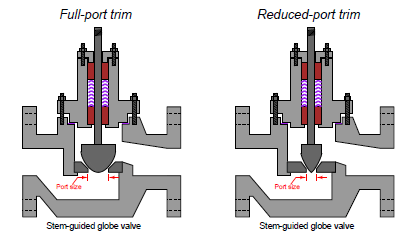

A practical solution to the problem of valve over-sizing – especially when larger flow rates will be required of the valve in the future – is to initially order the control valve with a body size suitable for the largest flow capacity it will need in the future, but equipped internally with reduced port (or restricted-capacity) trim. This means trim having smaller holes (“ports”) through which the fluid must flow. Such “reduced” trim is under-sized for the valve body, making the control valve’s Cv rating significantly less than it would be with normal-sized trim installed. The benefit of installing reduced-port trim in a control valve is that the flow capacity of the valve may be upgraded simply by removing the reduced trim components and replacing them with full-port (full-sized) trim. Upgrading a control valve’s trim to full-port size is significantly less expensive than replacing the entire control valve with a larger one.

Reduced-port trim for a stem-guided or port-guided globe valve takes the form of a new (smaller) plug and seat assembly. The seat is specially designed to match the plug for tight shutoff and good throttling behavior while having the necessary external dimensions to fit the larger valve body casting:

Reduced-port trim for a cage-guided globe valve often consists of nothing more than a new cage, having smaller ports in the cage than standard. Thus, reduced-port trim for a cage-guided globe valve may utilize the exact same plug and seat as the full-port trim for the same cage-guided globe valve: