Use of filter cells to improve selectivity

If the interfering gas(es) do not absorb any of the light wavelengths as our gas of interest, the selectivity will be total: the gas-filled detector will only respond to the presence of the gas we are interested in. Usually, though, process applications are not this simple. In most applications, the interfering gases have absorption spectra overlapping portions of the interest-gas spectrum. This means changes in interference gas concentration will be sensed by the detector (though not as strongly as changes in the concentration of the gas of interest) because part of the light spectrum absorbed by the interfering gas(es) will have a heating effect on the pure gas inside the detector.

An example of overlapping absorption spectra is found with the combination of carbon dioxide and acetylene gases:

As you can see, there is some common absorption between these two gas species toward the righthand side of the scale, around 700 cm−1 (approximately 14,000 nm). An NDIR analyzer equipped with a Luft detector filled with 100% of carbon dioxide gas will respond strongly to concentrations of carbon dioxide gas in the sample chamber, and weakly to concentrations of acetylene gas in the sample chamber. Since acetylene does absorb some of the infrared light wavelengths absorbed by carbon dioxide, acetylene gas has the potential to affect the Luft detector and make the analyzer “think” it is measuring slightly more carbon dioxide gas than it actually is.

One more addition to our NDIR instrument helps eliminate this problem: we add two more gas cells in the path of the light beams, each one filled with 100% concentrations of the interfering gas. For this particular example, we would fill each filter cell with a 100% concentration of acetylene gas, and the Luft detector cell with a 100% concentration of carbon dioxide gas:

These filter cells purge the light of those wavelengths normally absorbed by the interfering gas (acetylene) inside the sample cell. As a result, no amount of interfering gas in the sample cell will have any effect on the light exiting the sample cell, because those wavelengths have already been filtered out. If the filter cells were 100% effective in filtering all wavelengths specific to the interfering gas, there would be absolutely no light left to be absorbed by the interfering gas inside the sample cell, and therefore absolutely no effect of the interfering gas upon the Luft detector.

So long as our gas of interest exhibits absorption wavelengths not shared by the interfering gas (i.e. wavelengths of light unique to the gas of interest alone), these wavelengths will still be able to pass through the filter cells and into the sample cell where they will change intensity as the gas of interest varies in concentration. Thus, the detector now only responds to the gas of interest (carbon dioxide), and not to the interfering gas (acetylene).

As effective as this filtering technique is, it has the limitation of only working for one interfering gas at a time. If multiple interfering gases exist in the sample stream, we must use multiple filter cells to block those light wavelengths.

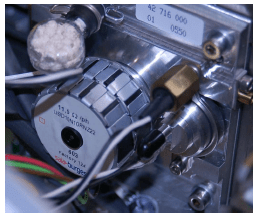

In this particular instrument (a Rosemount Analytical model X-STREAM X2), the chopper wheel is driven by a stepper motor:

The head of the infrared light source appears just to the right of the chopper wheel motor.