The “Achilles heel” of chromatography is the extraordinary length of time required to perform analyses, compared with many other analytical methods. Cycle times measured in the range of minutes are not uncommon for chromatographs, even continuous “on-line” chromatographs used in industrial process control loops! It is the basic nature of a chromatograph to separate components of a chemical stream over time, and so a certain amount of dead time will be inevitable. However, dead time in any measuring instrument is an undesirable quality. Dead time in a feedback control loop is especially bad because enough of it will cause the loop to self-oscillate.

One way to reduce the dead time of a chromatograph is to alter some of its operating parameters during the analysis cycle in such a way that it speeds up the progress of the mobile phase during periods of time where slowness of elution is not as important for fine separation of components. The flow rate of the mobile phase may be altered, the temperature of the column may be ramped up or down, and even different columns may be switched into the mobile phase stream. In chromatography, we refer to this on-line alteration of parameters as programming.

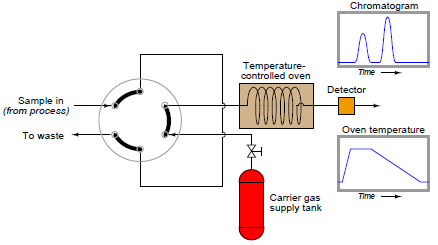

Temperature programming is an especially popular feature of process gas chromatographs, due to the direct effect temperature has on the viscosity of flowing gas. Carefully altering the operating temperature of a GC column while a sample washes through it is an excellent way to optimize the separation and time delay properties of a column, effectively realizing the high separation properties of a long column with the reduced dead time of a much shorter column:

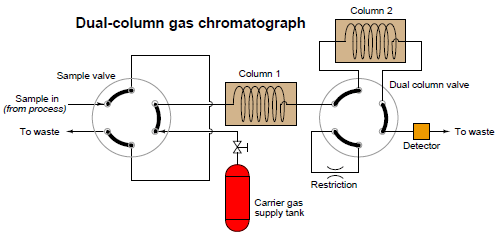

Another way to speed up the analysis time of a chromatograph is to design it with multiple columns and multiple switching valves, timing the valves so that only the fastest species travel through all columns, while slower species of chemical compounds bypass later column stages to exit through the detector first. The alternative is to force all species to elute through all columns (or one long column), which means the cycle time will be fixed by the slowest species present in the sample. To use the marathon analogy again, it’s like having to wait until the last person crosses the finish line before deciding how many fast and slow runners there were participating. If, however, we stop the race mid-way to shuttle slow runners to the finish line (because we already know who is slow), we can still let the fastest runners compete for the entire distance to determine who among them is the fastest:

A sequence for one type of dual-column gas chromatograph begins with the sample valve injecting a precise quantity of sample into the first column. In this illustration, the sample is comprised of 6 species labeled 1 through 6 in the order of their elution speed through the columns:

In the next step, the six species elute through column 1, with species 1 through 3 making it into the second column while species 4 through 6 are still residing in column 1:

At this point in time, the dual-column valve switches into bypass mode, trapping species 1 through 3 inside column 2 while allowing species 4 through 6 times to exit column 1 and pass through the detector:

In the last step, the dual-column valve switches back to its normal mode, allowing species 1 through 3 to elute through column 2 and pass through the detector:

The dual-column valve’s timed switching from normal to bypass and back to normal again permits the slowest species to skip past the second column, while the fastest species must elute through both columns for maximum separation. This dual column switching greatly reduces the total retention time of the sample without sacrificing the separation of the fastest species. A few noteworthy points must be raised about multi-column chromatographs. First, the example shown in the preceding diagrams is not the only type of multi-column chromatograph.

“Trapping” a series of sample compounds inside a column is not the only way to provide different compounds with different column paths for faster separation. Some multi-column chromatographs, for example, use “backflush” valves to reverse flow through one or more columns to avoid having the slowest species elute through all columns. This technique is used in applications where separation among compounds in the “slow” group is not important, since backflushing tends to reverse any separation that took place in the column previously.

The next point regarding multi-column chromatographs is that the dual-column valve timing must be precisely set according to the known retention times of the different species inside the different columns. In the example GC shown previously, this means the retention times of the transition species (3 and 4 in this case) through the first column must be precisely known, so the dual-column valve may be switched into bypass mode after species 3 exits the first column but before species 4 exits the first column. The retention time of the slowest species (6) must also be precisely known so that the dual-column valve will not switch back to normal mode too soon and route any of that species into the second column where it would take much more time to leave the system. A final point regarding multi-column chromatographs is that the order of species progression through the detector will not be fastest to slowest as with single-column chromatographs. In the dual-column GC shown previously, the slower group will exit first in order of speed (4, 5, 6), then the fastest group will exit last in order of speed (1, 2, 3).