Several different detector designs exist for process gas chromatographs. The two most common are the flame ionization detector (FID) and the thermal conductivity detector (TCD). Other detector types include the flame photometric detector (FPD), photoionization detector (PID), nitrogen phosphorus detector (NPD), and electron capture detector (ECD). All chromatograph detectors exploit some physical difference between the solutes (sample components dissolved within the carrier gas) and the carrier gas itself which acts as a gaseous solvent, so that the detector may be able to detect the passage of solute molecules among carrier molecules.

Flame ionization detectors work on the principle of ions liberated in the combustion of the sample components. Here, the assumption is that sample compounds will ionize inside of a flame, whereas the carrier gas will not. A permanent flame (usually fueled by hydrogen gas which produces negligible ions in combustion) serves to ionize any gas molecules exiting the chromatograph column that are not carrier gas. Common carrier gases used with FID sensors are helium and nitrogen, which also produce negligible ions in a flame. Molecules of the sample encountering the flame ionize, causing the flame to become more electrically conductive than it was with only hydrogen and carrier gas. This conductivity causes the detector circuit to respond with a measurable electrical signal. A simplified diagram of an FID is shown here:

Hydrocarbon molecules happen to easily ionize during combustion, which makes the FID sensor well-suited for GC analysis in the petrochemical industries where hydrocarbon composition is the most common form of analytical measurement. It should be noted, however, that not all carbon-containing compounds significantly ionize in a flame. Examples of non-ionizing organic compounds include carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and carbon sulfide. Other gases of common industrial interest such as water, hydrogen sulfide, sulfur dioxide, and ammonia likewise fail to ionize in a flame and thus are undetectable using an FID.

Thermal conductivity detectors work on the principle of heat transfer by convection (gas cooling). Here, the assumption is that sample compounds will have different thermal properties than the carrier gas. Recall the dependence of a thermal mass flowmeter’s calibration on the specific heat value of the gas being measured. This dependence upon specific heat meant that we needed to know the specific heat value of the gas whose flow we intend to measure, or else the flowmeter’s calibration would be in jeopardy. Here, in the context of chromatograph detectors, we exploit the impact specific heat value has on thermal convection, using this principle to detect compositional change for a constant flow gas rate. The temperature change of a heated RTD or thermistor caused by exposure to a gas mixture with changing specific heat value indicates when a new sample component exits the chromatograph column.

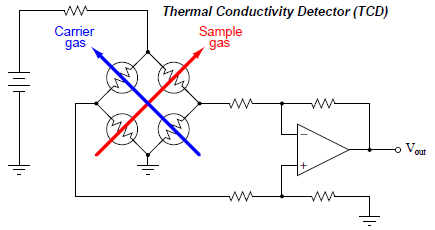

A simplified diagram of a TCD is shown here, with pure carrier gas cooling two of the self-heated thermal sensors and sample gas (mixed with a carrier gas, coming off the end of the column) cooling the other two self-heated sensors. Differences in thermal conductivity between gas exiting the column versus pure carrier gas will cause the bridge circuit to unbalance, generating a voltage signal at the output of the operational amplifier circuit:

This type of chromatograph detector works best, of course, when the carrier gas has a significantly different specific heat value than any of the sample compounds. For this reason, hydrogen or helim (both gases having extremely large specific heat values compared to other gases) are the preferred carrier gases for chromatographs using thermal conductivity detectors.