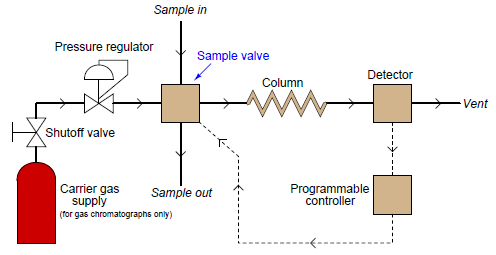

The most common type of chromatography used in continuous process analysis is the gas chromatograph, so named because the mobile phase is a gas (or a vapor) rather than a liquid. In a gas chromatograph, the sample to be analyzed is injected at the head of a very long and very narrow tube packed with solid and/or liquid material. This long and narrow tube (called the column) is designed to impede the passage of the sample molecules. A continuous flow of “carrier gas” washes the sample compounds down the length of the column, allowing them to separate over time according to how they interact with the stationary phase packed inside the column. A simplified schematic of a process gas chromatograph (GC) shows how this type of analyzer functions:

The sample valve periodically injects a very precise quantity of samples into the entrance of the column tube and then shuts off to allow the constant-flow carrier gas to wash this sample through the length of the column tube. Each component of the sample travels through the column at different rates, exiting the column at different times. All the detector needs to do is be able to tell the difference between pure carrier gas and carrier gas mixed with anything else (components of the sample).

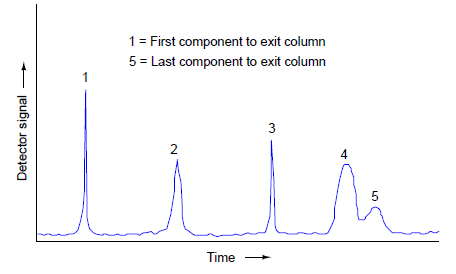

If we plot the response of the detector on a graph, we see a pattern of peaks, each one indicating the departure of a component “group” exiting the column. This graph is typically called a chromatogram:

Narrow peaks represent compact bunches of molecules all exiting the column at nearly the same time. Wide peaks represent more diffuse groupings of similar (or identical) molecules. In this chromatogram, you can see that components 4 and 5 are not clearly differentiated over time. Better separation of components may be achieved by altering the sample volume, carrier gas flow rate, carrier gas pressure, type of carrier gas, column packing material, and/or column temperature.