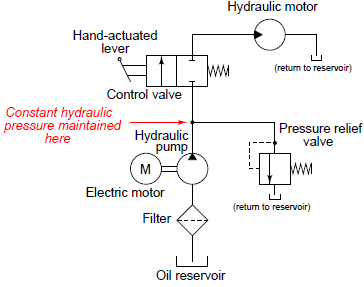

Hydraulic systems require more components, including filters and pressure regulators, to ensure proper operation. Shown here is a simple uni-directional hydraulic motor control system:

Note the placement of the pressure relief valve: it is a shunt regulator, bleeding excess pressure from the discharge of the hydraulic pump back to the reservoir. A “shunt” regulator is necessary because hydraulic pumps are positive displacement, meaning they discharge a fixed volume of fluid with every revolution of the shaft. If the discharge of a positive-displacement pump is blocked (as it would be if the spool valve were placed in its default “off” position, with no shunt regulator to bleed pressure back to the reservoir), it will mechanically “lock” and refuse to turn. This would overload the electric motor coupled to the pump, if not for the pressure regulating valve providing an alternative route for oil to flow back to the reservoir. This shunt regulator allows the pump to discharge a fixed rate of oil flow (for a constant electric motor speed) under all hydraulic operating conditions.

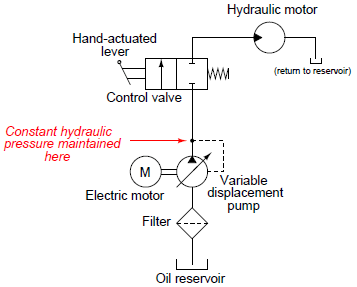

An alternative to using a shunt regulating valve in a hydraulic system is to use a variable displacement pump. Variable-displacement pumps still output a certain volume of hydraulic oil per shaft revolution, but that volumetric quantity may be varied by moving a component within the pump. In other words, the pump’s per-revolution oil displacement may be externally adjusted.

If we connect the variable-displacement mechanism of such a hydraulic pump to a pressure sensing element such as a bellows, in a way where the pump senses its own discharge pressure and adjusts its volumetric output accordingly, we will have a pressure-regulating hydraulic system that not only prevents the pump from “locking” when the spool valve turns off, but also saves energy by not draining pressurized oil back to the reservoir:

Note the placement of a filter at the inlet of the pump in all hydraulic systems. Filtration is absolutely essential for any hydraulic system, given the extremely tight tolerances of hydraulic pumps, motors, valves, and cylinders. Even very small concentrations of particulate impurities in hydraulic oil may drastically shorten the life of these precision components.

Hydraulic fluid also acts as a heat-transfer medium, and as such must be kept cool enough to prevent thermal damage to components. Large hydraulic systems are equipped with coolers, which are just heat exchangers designed to extract heat energy from the fluid and transfer it to either cooling water or ambient air. Small hydraulic systems dissipate heat at a fast enough rate through their components that coolers are often unnecessary.

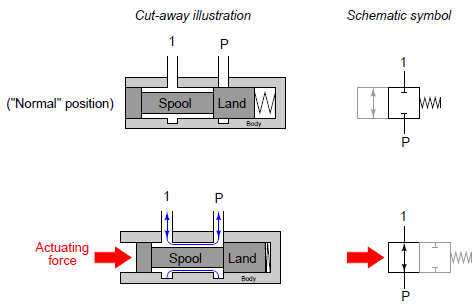

An interior view of a simple “2-way” spool valve such as that used in the hydraulic motor system previously examined reveals that cleanliness and temperature stability is important. The spool valve is shown here in both positions, with its accompanying schematic symbol:

Both the spool and the valve body it moves in are circular in cross-section. The spool has wide areas called “lands” that act to cover and uncover ports in the valve body for fluid to flow through. The precise fit between the outside diameter of the lands and the inside diameter of the valve body’s bore is the only factor limiting leakage through this spool valve in the closed state. Dirty hydraulic fluid will wear at this precise fit over time until the valve is no longer capable of sealing fluid in its “closed” position. Extreme cycles in temperature will also compromise the accurate fit between the spool and the valve body.